Mong – Tatars National Unity Through Song

The Cruise

On board a Turkish cultural cruise I took in July 2000 I met the much-loved Tatar singer Färidä Kudasheva, a small woman with a benevolent gaze, auburn hair, and the high cheekbones and round cheeks typical of Eurasian Turks. One evening after dinner Färidä apa – Auntie Farida, as she preferred to be called – gave a concert in celebration of her 80th birthday. When she began to sing, instead of smiling and looking each other in the eyes as

they had during previous concerts, the audience, tightly packed together in the ship’s stuffy hold, sat somberly without moving. Hints of tears glinted in people’s eyes. Their gazes were still, uncharacteristically disconnected from the present moment. The songs Färidä apa sang were slow in tempo and minor in key. A mournful accordion accompanied her voice. About halfway through her performance, Färidä apa stopped singing and explained that she had decided to sing only mongly jyrlar – mongful songs – that evening. After another hour, the concert ended. The Master of Ceremonies came on stage and thanked Färidä apa profusely for her performance. Then, people from the audience started presenting the singer with gifts. Before placing the gifts in her hands, smiling, their gazes once again connected to the people in their immediate surroundings, each person wished Färidä apa Happy Birthday and thanked her for the concert. She received each gift with a kiss or an embrace.

they had during previous concerts, the audience, tightly packed together in the ship’s stuffy hold, sat somberly without moving. Hints of tears glinted in people’s eyes. Their gazes were still, uncharacteristically disconnected from the present moment. The songs Färidä apa sang were slow in tempo and minor in key. A mournful accordion accompanied her voice. About halfway through her performance, Färidä apa stopped singing and explained that she had decided to sing only mongly jyrlar – mongful songs – that evening. After another hour, the concert ended. The Master of Ceremonies came on stage and thanked Färidä apa profusely for her performance. Then, people from the audience started presenting the singer with gifts. Before placing the gifts in her hands, smiling, their gazes once again connected to the people in their immediate surroundings, each person wished Färidä apa Happy Birthday and thanked her for the concert. She received each gift with a kiss or an embrace.

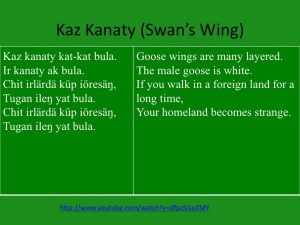

Click here to hear Kaz Kanaty

One middle-aged woman, who said she had grown up in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) among Russians, asked permission to speak in Russian. After implying that she didn’t know the Tatar language, the woman talked about the lyrics to Färidä apa’s songs. The woman said they reminded her of her childhood and how her äbi – Tatar for grandmother – used to listen to Färidä apa’s music. She explained that, after taking the cruise three times, she had come to understand the significance of the songs’ words. Several other audience members made similar statements regarding the memories Färidä apa’s songs conjured up. Everyone mentioned that hearing Färidä apa sing brought back recollections of listening to her songs on the radio as children in the company of now-dead relatives. Their speeches often nostalgically referred to the native villages in which most no longer lived.

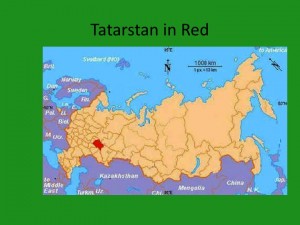

Russian Colonialism

The society on board the cruise ship provided an environment in which Tatars could be free to be Tatar without having to worry about offending Russians. Referred to as a mini-hadj, and embarked upon repeatedly like the hadj’s smaller stages, the cruise was an annual cultural event for constructing and reinforcing a not necessarily Muslim, post-Soviet Tatar identity. The small ship disembarked from Ufa and sailed along the Belyi and Volga Rivers to Kazan and back over the course of a week, stopping at sites of significance to Tatar culture along the way. Musicians staged nightly concerts, after which the cruise organizers held exclusive midnight banquets in the dining room while everyone else attended inclusive Tatar discotheques and spontaneous musical performances on deck.

Although a few passengers didn’t speak Tatar, those of us who did didn’t have to calculate whether or not it was appropriate to converse in that language. The repeated creation of this cultural space had an enduring effect on passengers, who would plan and save throughout the year in order to take the cruise again and thus renew the feelings of joy and belonging they experienced during it. Because they were able to take pleasure in being ethnically Tatar and to speak Tatar freely at the same time, the cruise reinforced Tatars’ generally held belief that culture resides in language. It encouraged people to engage in what they felt to be the most Tatar kinds of relations and provided them a forum to talk about, create, and experience mong.

The findings presented here are based on 18 months of field research between 1997 and 2006, primarily in Kazan, Tatarstan (Russia). My book, Nation, Language, Islam: Tatarstan’s Sovereignty Movement, published in 2011, elaborates upon them, drawing on interviews about mong and other topics with several hundred of people and archival sources.

Mong is a generalized feeling of grief-sorrow, a type of melancholy song, the sorrowful melodies that animate the melancholy songs, the sentiment singers singing those songs tap into and transmit, the emotion audience members experience while listening to them, and a subject of ideological talk.

The Songs

Always sung in a minor key and often accompanied by the accordion, mongful songs are marked by long-held, deeply resonant notes carried best by strong, clear, versatile voices that sonorously sound the songs’ sad lyrics. Typical mong lyrics concern feelings of sorrow and loss expressed metaphorically through an emotional description of a scene from nature. Their lack of specificity allows them to belong to the nation as a whole, as opposed to individual people. In being laden with an untranslatable mournful nostalgia, mong bears a similarity to the Portuguese musical genre fado. And while mong’s musical qualities differ profoundly from those of the American blues, young Tatars aware of parallels between US and Soviet history sometimes refer to mong as “the Tatar blues.”

Mong taps into, produces, and reproduces feelings that unite Tatar-speakers as a nation who have suffered collectively. It successfully generates a feeling of collective suffering because individuals are encouraged to understand mong in diverse ways. This flexibility allows Tatars to experience a feeling of collective inclusiveness and separates them ideologically from people they perceive as comprising an undifferentiated “Russian sea.” Mong provides a revealing insight into the structure of Tatar emotions. Different from other Tatar social situations, when listening to mongly jyrlar, it is permissible to withdraw your gaze and allow tears to well up in your eyes. Listeners disconnect their attention from their surroundings and contemplate the grief-sorrow of their inner worlds. Thus, while mong is an intensification of the essence of normative Tatar emotionality, it is also separate from daily behavior norms that dictate attentiveness and a focus on the positive.

Mongly jyrlar are highly conservative in form. Mong is still most frequently produced when groups of people sit around a table drinking tea and singing. Despite mong’s role as an everyperson’s practice, like other surviving Soviet folk arts, its songs have been fixed as texts in books, professionalized by conservatory-trained artists, and commoditized in recordings. While singing mongly jyrlar is losing popularity among urban youth living at a remove from the rhythms of village life, it nevertheless remains part of the habitual activities of their city-dwelling parents and those relatives who remain in the villages. Moreover, even young urban Tatar-speakers feel that mong is a core feature of Tatar identity.

The Spirit

Perhaps mong’s most significant quality is that it is generally understood to be something Russians do not have, nor care to learn about. Tatar-speakers often say that Russians do not have a word equivalent to mong and therefore they cannot they understand what it means. However, recognizing mong does not require knowledge of Tatar, just curiosity about its existence. Thus, saying that Russians have no word for mong in actuality glosses Russian indifference to mong and the insult to Tatar cultural values that that indifference implies. This mirrors other relationships between Tatars and Russians, colonial in that Tatars know all about things Russian, while Russians are largely unaware of any but the most superficial aspects of Tatar culture. Though mong is not part of Tatar culture that Tatars feel they can explain while speaking Russian, mong is nevertheless rendered in Russian as “melody” and occasionally as “nostalgia.”

In 2000, Sveta apa, a teacher a school in Kazan, Tatarstan’s capital, hosted a tea-drinking event and asked her teenage students sing. At her request, the students happily sang the unofficial Tatar national anthem, Tugan tel [Native Tongue], based upon the best-known work by pre-revolutionary Tatar poet Gabdullah Tukay. Then, Sveta apa asked the students to sing a mongful song. The students protested that they did not know any. Sveta apa scolded them, saying, “You need to learn mongful songs. Otherwise, who will teach this mong to your children? You know,” she continued, “When I have difficult moments, I sing.” Then, she began to sing alone.

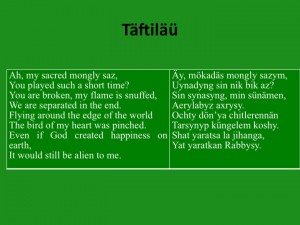

She chose the song Täftiläü, in which, she informed me on a later occasion, “all the mong of the Tatar people, all its past, all its grief-sorrow and the painful existence that has accumulated through the centuries has been placed.” As she sang, the smiles dropped off the students’ faces. Their eyes got misty and their expressions became mournful and distant. The only ones somewhat unaffected by the song were the class’ sole boyfriend-girlfriend couple, who were flirting with each other. But, by the end of the song’s three verses even the girlfriend had developed a removed gaze. These teenagers were urban-dwelling. Unlike their Tatar elders, who grew up in villages and only started speaking Russian once they migrated to Kazan to go to university, they were both physically and culturally distanced from mong as a regular practice. However, through even relatively infrequent experiences of mong, these children felt it and existed, at least intermittently, in a discursive world shaped in part by its grief-sorrow.

A year later, Sveta apa agreed to let me interview her about mong. Around 60 at the time, Sveta apa was a respected singer and a hadji. She had visited Mecca, fasts during Ramadan and observes other Muslim prohibitions – like that against drinking spirits – but sees no conflict between the teachings of Islam and singing.

Sveta apa began the interview by asserting that mong is a quality Americans don’t have, due to our diversity, but also something that does not exist in the English, German, French, or Arabic languages, and consequently – she implied – not in speakers of those languages. She suggested that Russians don’t understand its meaning either since mong is rendered as “melody” in Russian. She insisted that mong does not belong to individuals, but instead is an attribute of the whole Tatar people.

Mong both resides in the people as a whole and, through its reproduction, recreates the collective. In Tatar villages today, as in Sveta apa’s accounts of her childhood, frequent back and forth visiting between households strengthens collectivist connections. Thus, when Sveta apa spoke of her parents singing, she described scenes in which several households gathered together. The social unit that produces and reproduces mong consists of a loosely bound and shifting community of relatives, neighbors, and co-nationals in whom mong is considered to reside.

Energy From The Heavens

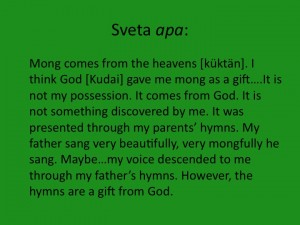

Although Sveta apa considers mong and iman – Muslim faith – to be neighboring green roots of one tree, she once described mong to me in a way that seemed to embrace pre-Islamic Turkic beliefs according to which the supreme being is the Sky God, Kük-Tängri. Speaking more Russian to me this one time than ever before or afterwards, Sveta apa treated mong as if it were a supernatural force from on high.

I sing and mong flows. From where I don’t know. (She gestured towards the sky.)….It is melody and energy…

Later, Sveta apa explained how she had received mong through the “hymns” her parents sang.

This conveys how mong has been passed down from one generation to another, as well as how it is reproduced among people of the same generation. Singing mongly jyrlar transmits knowledge of the songs and how to sing them, while simultaneously producing the affect of national unity in shared suffering. Sveta apa also described how lyrics about nature pertain to actual histories of suffering.

Mong is therefore historical for at least three reasons. It conjures up a past prior to and better than the pain of the present. It has been used as a tool to live through difficult moments in Tatar history. And it reminds singers and listeners of the times when Tatar people needed mong most.

Allegorical History

Even though Tatars speak of mong as an expression of Tatar historical tragedy, the lyrics to mongful songs never concern history. This is remarkable because Kazan Tatars often talk about the horrors perpetuated when Ivan the Terrible conquered Kazan in 1552, such as how the Volga River flowed red with blood and how, later, Muslim Tatars were forcibly, sometimes without their knowledge, baptized with water from that river.

Baptism is considered a violation, among other reasons, because baptized Tatars’ names were changed to Russian ones. They lost the ability to identify members of their families.

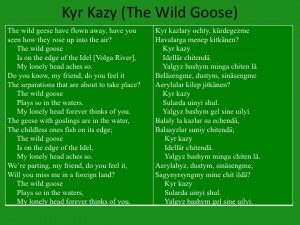

This is part of a larger discourse about how Russian conquest, colonization, and subsequent Soviet rule served to forcibly assimilate masses of Turks living in Eurasia. Tatars also describe how their forefathers were kept off well-watered, fertile land after 1552 and barred from pursuing trade until the 18th century. However, mongful songs don’t address these themes. Rather, they convey the burden of existence [tormysh avyrlygy] allegorically and frequently concern separation [aeru], a euphemism for death. Tatars see the pain of death separation clearly in lyrics about how the wild goose that landed on the lake has flown away.

The Gulag

Invoking mong to convey unspecified moments of historical tragedy allegorically may mask tragedies that have occurred in real historic time. Examining how Soviet history personally affected Sveta apa suggests a more conventional explanation for why mong signifies both nostalgia for an idyllic past and grief-sorrow. Sveta apa’s father was a talented singer of mongly jyrlar. He also fought in the Soviet Armed Forces against the Nazis during World War II. After the war, Sveta apa’s father was arrested – probably as a “traitor” for having been interned in a German POW camp – and sentenced to 25 years in a labor camp outside Irkutsk, in Siberia. He was freed in the mid-1950s after serving ten years of his sentence, at a time when the majority of the Soviet Union’s slave labor force was released following Stalin’s death in 1953. During our interview Sveta apa informed me that her father had been able to maintain his inner world while in the Gulag, and that he had remained a human being – a keshe – despite the experience of being there. “It seems he was able to preserve himself,” she explained. “This is connected to those mongly jyrlar.”

Sveta apa described the awakening of her own mong as occurring while her father was serving in the Soviet Army. She said she had begun to sing at the age of seven, during the war. At the time, there was still no television, no radio, and no electricity in the village. The villagers used kerosene lamps for light, she told me. Singing was the primary form of entertainment. After her father’s arrest, when Sveta apa would have been in her early teens, she traveled to Siberia to visit him at least once. Though mong possessed Sveta apa early in childhood, its full power as an expression of grief-sorrow seems to have been revealed to her after her father returned from Siberia. Such experiences – transitions from innocence to awareness – are in fact a collective phenomenon for Kazan Tatars and indeed for people who lived through the Soviet Union. Every family I got to know suffered at least one such tragedy.

Conclusions

Mong demonstrates how Tatar nationalism works. Tatars say that mongful songs contain the tragedy of the nation’s history. However, unlike other forms of Tatar verbal expression, mong never refers to the particular events Tatar-speakers avow make their nation’s history a tragic one. Rather, it represents tragedy allegorically. The very inflexibility of mong’s form, along with the song lyrics’ non-specificity, makes multiple interpretations possible. Tatar-speakers almost universally say they experience mong the same way and consider themselves to be talking about the same phenomenon when they discuss it. However, they use diverse understandings of mong as a way to express their individual worldviews. Tatars see no inconsistency in this, considering it both common sense and common knowledge that variation occurs. Mong thus provides a counterexample to commonly accepted theories of how people imagine themselves as co-nationals.

Shopping Cart

Your shopping cart is empty

Visit the shop